Introduction

For patients facing cancer – especially advanced or recurrent forms – the search for new hope often extends beyond conventional treatments. In recent years, drug repurposing has emerged as a promising strategy. This approach looks at existing medications (often well-known drugs for other ailments) and tests them against cancer. The idea is compelling: if a safe, affordable drug might slow down a tumor, patients want to know. We also recognize the emotional and physical weight of this journey. The goal of this article is to empower you with understanding – explaining the science and regulatory landscape of repurposed drugs – while honoring the hope that drives one to explore every option. We’ll begin by examining how and why certain drugs become repurposed for cancer (sometimes with FDA approval, sometimes without), and then focus on fenbendazole: a dog dewormer that has attracted interest as an unconventional cancer therapy. Throughout, we maintain a scientific yet empathetic tone – because facts and compassion are both vital for those navigating difficult decisions.

Drug Repurposing in Cancer: Scientific and Regulatory Landscape

Drug repurposing (also called drug repositioning) means finding new therapeutic uses for old, already-approved drugs. In oncology, this is a rapidly growing field¹. The appeal is understandable: developing a brand-new cancer drug from scratch can take over a decade and immense cost, but an existing drug (with safety data in patients) can often be brought to trials faster and cheaper¹.

From a regulatory perspective, repurposing can happen in two ways: through off-label use or through formal clinical trials leading to a new approved indication. In the United States, once the FDA has approved a drug for any condition, physicians are generally allowed to prescribe it for other purposes if they judge it medically appropriate – this is known as off-label prescribing. Oncology is one field where off-label drug use is especially common. In fact, studies have found that anywhere from 13% to 71% of adult cancer patients end up receiving at least one off-label medication during treatment².

Why would a doctor or researcher consider repurposing a non-cancer drug for cancer in the first place? Often, it starts with an unexpected observation in the lab or clinic – for example, patients taking a certain medication for another condition seemed to develop less cancer, or a laboratory screen found that a cheap generic drug can kill cancer cells in a dish. Because of these clues, scientists then dig deeper. Over time, a surprising number of everyday drugs have shown potential activity against cancer cells. These range from metabolism regulators to anti-parasitic agents.

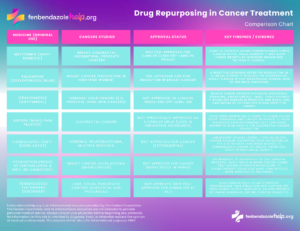

Table 1. Examples of Repurposed Drugs in Cancer Therapy

Fenbendazole: From Pet Dewormer to Cancer Buzzword

Fenbendazole is a benzimidazole anthelmintic – in simple terms, a veterinary drug that treats parasitic worms. It has long been used in animals like dogs and livestock. It is not FDA-approved for use in humans. Public interest in fenbendazole exploded following viral anecdotes like that of Joe Tippens, who attributed his cancer remission to the drug (though he was also receiving immunotherapy)¹¹.

Despite questions about causation, many patients with advanced cancers – particularly those with few conventional options – began self-administering fenbendazole. A South Korean study found that nearly all patients using antiparasitic drugs like fenbendazole did not inform their doctors, though most perceived a benefit and reported few side effects¹².

What Science Says: Preclinical Evidence

Scientific studies have shown that fenbendazole interferes with microtubule formation – structures crucial to cancer cell division – much like some chemotherapy agents. It also activates tumor-suppressor proteins (like p53), disrupts glucose metabolism, and promotes multiple cell death pathways. In animal models, tumors grew more slowly with fenbendazole treatment, and cancer cells resistant to traditional chemotherapy (like 5-FU) were killed by it¹³.

The Absence of Human Trials (and Why It Matters)

Despite promising lab and animal results, no clinical trials on fenbendazole in humans have been completed. This means we lack data on dosage, interactions, and long-term safety. Some researchers believe its status as a veterinary drug makes it hard to fund trials, since there’s little profit motive for pharmaceutical companies¹⁴.

Safety Considerations and Expert Guidance

Fenbendazole appears low in toxicity in animal studies and self-reports, but it’s not without risk. Since it’s processed through the liver, patients undergoing chemo or with liver involvement may face complications. Also, veterinary formulations may contain additives that are not safe for humans. Patients should always consult their oncologist before trying unapproved treatments. Open communication helps ensure monitoring, reduces harm, and allows collaboration or documentation of results.

Conclusion: Balancing Hope with Evidence

Fenbendazole reflects both the power and the pitfalls of drug repurposing. The science is compelling, but incomplete. Until human trials are conducted, it remains an experimental therapy. Still, it offers hope – not as a miracle cure, but as a possible future option worth studying. Patients deserve to understand both the risks and the possibilities. In the journey of healing, information is one of the most powerful tools.

References

- Pushpakom S, et al. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019.

- Conti RM, et al. Prevalence of off-label drug use in oncology: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol. 2016.

- Morales DR, Morris AD. Metformin in cancer treatment and prevention. Ann Transl Med. 2015.

- Rajkumar SV. Thalidomide in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003.

- Cummings SR, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1999.

- Kim DJ, et al. Itraconazole as an anti-cancer agent. Cancer Cell Int. 2013.

- Rothwell PM, et al. Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010.

- Dogra SK, et al. Flubendazole-induced cell death in leukemia cells. Sci Rep. 2017.

- Sotelo J, et al. Autophagy inhibition in glioblastoma treatment. Oncotarget. 2013.

- Dogra SK, et al. Fenbendazole acts as a microtubule destabilizer and causes cancer cell death. Sci Rep. 2018.

- PolitiFact Health Initiative. Fact-check on cancer cures and dewormers. 2022.

- Kim HJ, et al. Survey of Korean cancer patients using non-prescription anthelmintics. Integr Cancer Ther. 2022.

- Kim JY, et al. Fenbendazole triggers multiple pathways of cell death in resistant colorectal cancer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2022.

- Nguyen J, et al. Fenbendazole’s pharmacology and rationale for repurposing. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2023.